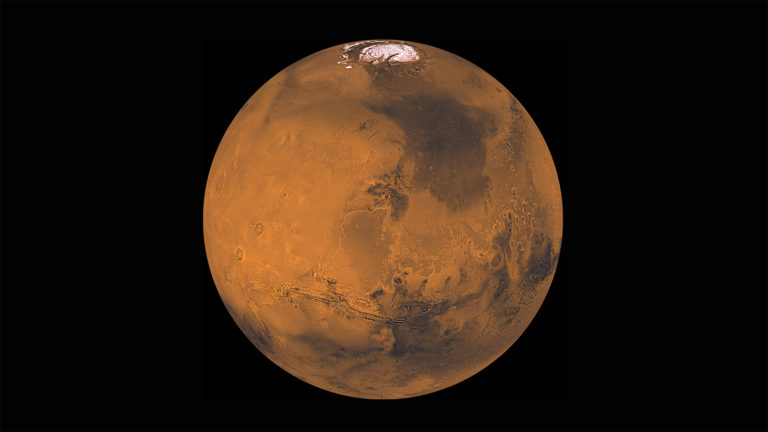

A mission to Mars would be, for lack of a better term, really really hard.

Not only will it be the farthest any human being has ever traveled – more than 54 million kilometers away – but it will also involve employing the most advanced technology we have, and then some.

The journey itself is going to be wrought with danger: between here and Mars, the astronauts will be bombarded by high-levels of cosmic radiation. As if that wasn’t bad enough, astronauts will also lose a good amount of bone density, and that’s only the beginning, we haven’t even talked about the psychological impact it will have on those brave souls.

With our current technology, a mission to Mars would take at least eight months one-way, and another 8 months going home. During the journey, the astronauts will have to contend with the idea that they are traveling through literal empty space, with only their spacecraft and their suits to keep them alive. Communications between them and Earth will take about 20 minutes to send, and another 20 minutes to receive. In short, they will be completely and utterly alone.

And we haven’t even begun talking about the equipment we need.

Wait So, Why Go To Mars in the First Place?

Perhaps the most obvious reason to go to Mars, other than Mankind’s incessant desire for exploration, is the scientific knowledge we can gain from the entire endeavor: from researching new spaceship engines and developing life support systems to creating unbelievably durable building materials, every step of the Mars mission will provide us with new technology, new information, and new ways of seeing our Universe.

The search for life aside, studying Mars from a planetary perspective will also help us give a better glimpse of how planets work, their evolutionary process, their atmospheric systems, and basically find ways to improve upon our own planet.

But the search for life, however, is the key component, and basically the entire raison-d’être, of a mission to Mars. Because of its similarity to Earth, finding and studying how life can exist outside of Earth will give us critical information on the how’s and why’s of our humanity, and maybe even give us ideas on taking that next step in our biological evolution.

So, what do we need to get ourselves to Mars?

Proper Training

Out of all the islands in the North of Canada, none are as important or as critical as Devon Island. Without Devon Island, a lot of our current research on the atmosphere of Mars, the Mars rover, and other Martian surface-related issues, wouldn’t exist.

But if you’ve never heard of Devon Island before, don’t worry; neither have a lot of people.

That’s because Devon Island is so inhospitable, so inaccessible, and so hostile to most forms of life on Earth that there really is no reason to visit it. This barren piece of rocky landscape, however, is a perfect analog for the Martian surface. This has made it a haven for scientists looking to test out Mars equipment and preparing for whatever the Red Planet might have in store.

To get to Devon Island, you’ll need to take around seven flights, some commercial and some private, and the whole journey will take around 3 days. But is it worth it? Well, only if you enjoy daily sub-zero temperatures and a Polar desert view, or if you’re training to be an astronaut.

Scientists used Devon Island back in 2007 as a temporary home in an attempt to simulate living and working conditions on Mars. During their 4-month stay, they conducted 20 scientific studies, all aimed at determining how future astronauts will survive the Martian landscape. Every summer, NASA descends on Devon Island’s Haughton Crater, considered to be the best Mars Analogue site on Earth, for a round of botanical, geological, microbiological, and hydrological studies in the hopes of furthering our understanding of the Red Planet.

One of the most important experiments they run on Devon Island involve the growing of vegetables on Martian soil. Because constant resupplies from Earth isn’t feasible, astronauts on a mission to Mars must be able to grow their own food, which is problematic because Martian soil doesn’t have the beneficial microbes that help plants grow, nor the nutrients essential for their survival.

However, scientists both on Devon Island and the International Space Station are figuring out ways to plant food both in space (in special soil pods) and on Mars. So far, they’ve been able to grow leafy green vegetables like lettuce and cabbage. Maybe not the most balanced diet, but when combined with potatoes (another potential space and Mars mission staple), this could be enough to sustain astronauts for long-distance missions, or prolonged stays on the Red Planet.

Sci-Fi Tech

Government agencies and private corporations are busy researching, designing, developing, and building some pretty impressive technology to help our future astronauts get to Mars as well as survive its harsh landscape. Ideally, this technology can also be used to start a permanent colony on the Red Planet, although that might be a few decades away.

While the technology to make all of this possible technically exists, applying it into hardware still needs a bit more time.

One of the first things we need to build are spaceships. At the forefront of this are NASA, the European Space Agency, and Elon Musk’s SpaceX program. Each organization is cooperating with some of the best minds on the planet to figure out how to get to Mars, and how to do it safely and in the fastest way possible.

One of the first things they’re looking into is building a spaceship that can be powered by an alternative fuel. Our current stock of rockets still rely on a combustive mixture of solid and liquid fuel to literally blast a spaceship into orbit. It’s an effective, albeit ineffective, method to get us from the ground and into orbit, but we’ll need something a little more sustainable to ferry our astronauts more than 50 million kilometers away.

From nuclear reactors and other exotic-fuel engines to solar power, scientists are trying to figure out the most efficient way to travel through space without the need for traditional chemical fuels, which are not only heavy and bulky to use, it’s also dangerous. Any tech that can eliminate this flight risk becomes a priority when you’re traveling on a spaceship.

Beyond that, these agencies are also busy creating building materials that are lightweight, reusable, and easy to assemble so that astronauts can build temporary habitats on Mars. Prefab shelters on the Red Planet need to be made of sterner stuff than the ones we have on Earth, not only to withstand subzero temperatures, but also bracing windstorms that can send debris hurtling through the air at breakneck speeds. Luckily, we have Devon Island to test all that stuff out.